什么是高级英语阅读?(我之浅见)

发布于 2021-04-09 21:16 ,所属分类:知识学习综合资讯

“高级英语阅读”这门课我前后讲了三十多年,再加上“西方文化名篇选读”、“英语阅读与欣赏”,我对这门课还是有一点心得的。早在1996年,我第一次总结了自己对于英语阅读“覆盖范围(层面)”的理解,列出了阅读中应该关注的26-28个层面/方面。再往后,我提出了阅读教学的“‘三文’模式”:

文字:微观或基础语言知识,包括词汇、语法等;

文学:语言艺术层面——包括文章的文体、风格、修辞及写作技巧等诸方面——的知识;

文化:与社会生活相关的各个方面知识。

可以这样说:没有“文字”不行,没有“文学”不全,没有“文化”不算。换一种更容易懂的表达方式:没有“文字”,我们根本理解不了阅读内容;没有“文学”,我们无法全面、深入地理解阅读内容;没有“文化”,我们的所有阅读活动或行为就没有了任何意义。

单纯这样说自然显得抽象且乏味。我们还是拿一篇文章做一个示范。(我绝无意告诉诸君我的方式有多么的先进或高级。我只是想告诉大家我自己是怎样进行阅读的。)

下面这篇文章节选自A Book for All Readers,其作者Ainsworth Rand Spofford曾任美国国会图书馆——世界上最大的图书馆——馆长长达33年(1864-1897)之久,对于书和读书自有非常人所能获得的理解和表述。

(补:四十几年前我读中学的时候,一次一位来代一节数学课的刘姓老师说过“不了解作者的阅读从根本上就不能叫做‘阅读’”。当时觉得这位老师有些故弄玄虚,甚至胡说八道——我们这些农村的娃儿到哪儿去了解著书者的背景资料。我记住这番话的原因是它的“悬”或不切实际。但此后的几十年里,我则发现这就是读书的一个“秘笈”。)

When we survey the really illimitable field of human knowledge, the vast accumulation of works already printed, andt he ever-increasing flood of new books poured out by the modern press, the first feeling which is apt to arise in the mind is one of dismay, if not of despair. We ask – who is sufficient for these things? What life is long enough– what intellect strong enough – to master even a tithe of the learning which all these books contain? But the reflection comes to our aid that, after all, the really important books bear but a small proportion to the mass. Most books are but repetitions, in a different form, of what has already been many times written and printed. The rarest of literary qualities is originality. Most writers are mere echoes, and the greater part of literature is the pouring out of one bottle into another. If you can get hold of the few really best books, you can well afford to be ignorant of all the rest. The reader who has mastered Kames’s “Elements of Criticism,” need not spend his time over the multitudinous treatises upon rhetoric. He who has read Plutarch’s Lives thoroughly has before him a gallery of heroes which will go farther to instruct him in the elements of character than a whole library of modern biographies. The student of the best plays of Shakespeare may save his time by letting other and inferior dramatists alone. He whose imagination has been fed upon Homer, Dante, Milton, Burns, and Tennyson, with a few of the world’s master-pieces in single poems like Gray’s Elegy, may dispense with the whole race of poetasters. Until you have read the best fictions of Scott, Thackeray, Dickens, Hawthorne, George Eliot, and Victor Hugo, you should not be hungry after the last new novel, – sure to be forgotten in a year, while the former are perennial. The taste which isonce formed upon models such as have been named, will not be satisfied with the trashy book, or the spasmodic school of writing.

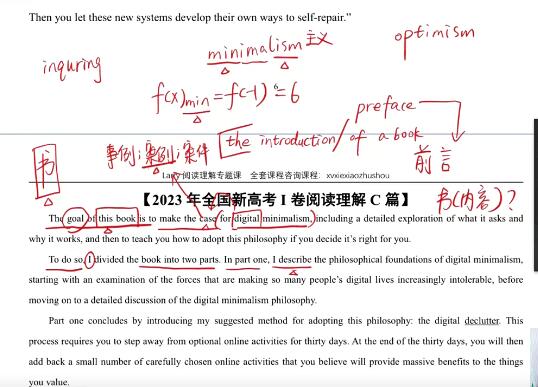

在读完第一句话“When we survey the really illimitable field of human knowledge, the vast accumulation of works already printed, and the ever-increasing flood of new books poured out by the modern press, the first feeling which is apt to arise in the mind is one of dismay, if not of despair”后,我首先可以基本确定的是:这是一篇“杂文”(essay),而非“散文”(prose)或“论文”(thesis/dissertation)。

根据是什么?

散文是用来抒情——抒情散文——或是叙事——叙事散文——的,而这句话不是。论文是用来严肃和认真地探讨——所以一般不能用第一或第二人称——自然界或社会里某个具体的现象、问题或发现。由于没有正常的作家会先用杂文的笔法开篇然后再转入散文或杂文,所以可以确定这个篇章整体上是杂文。

(补:欧洲文学或文章史上的杂文是近代的产物。最早写杂文的是法国的蒙田,最早写杂文的英国人是弗朗西斯.培根,都是在十六世纪开始的。)

杂文是用来阐述作者的观点或是想法的。写杂文的时候,作者不会像写抒情散文那样“纵情”或写叙事散文那么“有故事”,也不用像论文那样“重证据”——只要在提出观点后“讲理”或“重逻辑”,当然也可以讲“道德”或“情感”。

(补:“理性”、“道德”、“情感”是杂文中支撑观点的三大“法宝”。)

在确定了这是一篇杂文以后,下一步我们要做的是找出作者的观点。当句子是复合句的时候,作者想说的话通常在主句——the first feelingwhich is apt to arise in the mind is one of dismay, if not of despair(可能产生的情感即便不是绝望也是沮丧)。结合前半句,我们知道这句话作者想说的是:“‘学海’太‘无涯’了,想想就肝儿颤。”

首句就把观点“开门见山地亮出来”,这是“大学英语四六级考试”的水平。而且“书太多了,读不过来”这句话太常识了,所以不应该是作者的“主旨”。作者接着就丢出了一套问题:We ask – who issufficient for these things? What life is long enough – what intellect strongenough – to master even a tithe of the learning which all these books contain?(谁配得上这些东西?谁的寿命够长——智力够强——到能读完其中的十分之一?)显然这是前面观点的“延续”,而且更证明了这都是在为了“正主”的“登场”造声势。

如果此文是篇“考题级别”的文章,第三句的“But”极有可能直接引出文章的主旨:否定了前文的观点后,正主堂而皇之地登场。然而,这不是一篇那种类型——该说是“水平”——的文章。作者接着说的是…the reflection comes to our aid that,after all, the really important books bear but a small proportion to the mass(“替我们说话”——对我们有利——的回顾性总结结果是:好书只占很小的一部分。)随后的三句话解释了这种现象出现的原因:Most books arebut repetitions, in a different form, of what has already been many timeswritten and printed. The rarest of literary qualities is originality.Most writers are mere echoes, and the greater part of literature is the pouringout of one bottle into another.(多数的书都是在重复别人的东西。文人最稀有的属性是原创精神。多数作家就是在来回地“灌瓶子”。)

(提示:由于这里出现了两个Most引导的句子,二者自然是并列关系。这种结构表达的显然不会是文章的“主旨”。)

在经过几番铺垫后,“正主”终于“登堂入室”了:If you can gethold of the few really best books, you can well afford to be ignorant of allthe rest.(如果你能找到真正的好书,所有其它的就都可以“秒杀”了。)

这才叫“观点”!我们听到的一般性规劝都是:尽可能多读。可这位却告诉我们:只挑好的读,别理其它的!(这已经是“文化”层面的内容。)

什么是大师?敢说别人不敢说的话——当然是正确的话——这就是大师。(今天在与同事聊到了这个话题:我读本科的时候,特别尊敬的一位老师一再建议我去听胡宗鳌先生的文学课。原因只有一个:他敢讲!“敢讲”是要有“底气”的。胡先生是钱钟书先生的研究生,自然有这样的底气。又及:我推荐学生读钱穆先生那本二百多页的《中国通史》。为什么?观点和结论十分简洁明了,从不拖泥带水。)

或许会有人问:你凭什么说这句是主旨句?因为前面的都不是,因为后面的也不可能是——后面的是一些并列的例证。它们只能一起支持前面的“观点”。

总结一下这篇的“开篇特色”?

首先是从我们所认同的观点“切入”。这是一个十分重要的“点”。一下子抓住读者的最有效手段(之一)就是把他(们)的心里话说出来。

其二是层层铺垫,把话说透了:

书多到吓人的程度→读不过来;

真正的好书太少→多数书是重复/多数作者的作品了无新意,

怎么办?

答案:只读该读的(那小部分)

其三是善于用并列(排比)结构来强化表达的效果:

What life is long enough – what intellectstrong enough…

Most books are... Most writers are …

要提醒的是,使用这种结构的时候要谨慎。该选几项要反复斟酌。本篇作者每个结构里只选了两项。为什么?只有两项。

以第一个为例。影响读书数量只有两个因素:寿命长短决定着读书时间;intellect(知识智力)——而非intelligence(天生的智力)——水平决定着读书速度。

同样的理念和技巧也体现在后面的部分。作者列举了修辞(演讲)方面的Kames(卡莫斯勋爵)的 “Elements of Criticism;”传记(历史)方面Plutarch(普鲁塔克)的 Lives(名人传);戏剧方面的 Shakespeare,诗歌方面的Homer(荷马), Dante(但丁), Milton(弥尔顿), Burns(彭斯), 和 Tennyson(丁尼生),小说方面的Scott(司各特), Thackeray(萨克雷), Dickens(狄更斯), Hawthorne(霍桑), George Eliot(乔.艾略特), and Victor Hugo(雨果)。以这些大师们作品为例证明:sure to be forgotten in a year, while theformer are perennial(一般的作品一年就会忘,而大师们的作品却会历久弥新)The taste whichis once formed upon models such as have been named, will not be satisfied withthe trashy book, or the spasmodic school of writing(读大师作品形成的品味再也忍受不了垃圾作品)。

(篇幅有要求,只能先写到这里)

![徐磊高考英语2021高考英语写作之“特殊班”[百度云资源]](https://static.kouhao8.com/cunchu/cunchu7/2023-05-18/UpFile/defaultuploadfile/230425ml/188-1.jpg?x-oss-process=image/format,webp/resize,w_88/crop,w_88,h_88,g_nw)

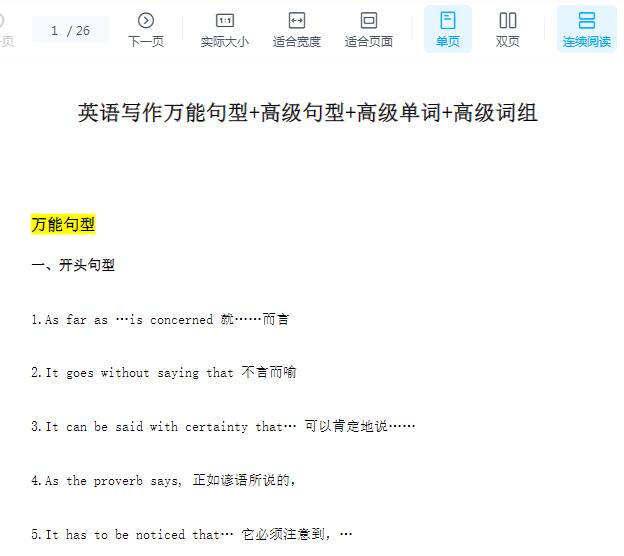

相关资源